Lorna McNaughton, LIC reproduction scientist, looks at the importance of low- methane bulls as we move towards reducing emissions.

Ruminant livestock emit methane, mostly through burps, as part of the digestion process, and the amount produced depends on how much feed is eaten and what type.

It’s estimated dairy bulls burp every 90-120 seconds, so reducing this ‘gassy’ emission is a focus for many New Zealand breeding companies, including LIC.

Breeding is one tool that could be used to help dairy farmers reduce emissions on their farms. Methane emissions have been shown to be heritable (0.10 to 0.20), a necessary step on the pathway to develop a breeding value. The degree of heritability is similar to that of somatic cell score (0.15), but lower than milk traits (0.31 to 0.36).

A joint project between LIC and CRV, funded by the New Zealand Agricultural Greenhouse Gas Research Centre (NZAGRC), aims to measure methane from dairy bulls entering the sire proving schemes of both breeding companies.

A significant trial is now taking place, part of it at LIC’s Chudleigh Farm, east of Hamilton, New Zealand. The project’s first stage was to design and develop methods that enabled the emissions of 300 to 350 bulls to be measured each year. To do this, a single pen was set up with a Greenfeed machine to measure methane, and feed bins allowed each bull’s intake to be measured.

Selection of feed type was important. The low dry matter of grass, or grass silage, together with variations in quality, meant that alternative feeds needed to be identified. Lucerne hay cubes were selected because they were a forage high in dry matter.

This also meant bulls only needed their feed bins topped up once or twice per day, with quality relatively consistent from year-to-year. A small quantity of pelleted feed was available in the Greenfeed machine to entice the bulls to visit the machine.

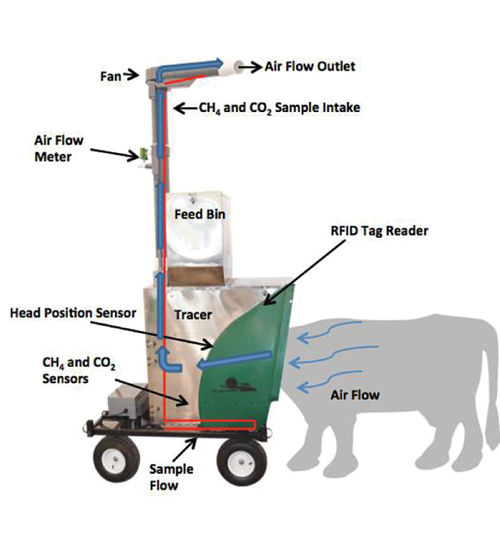

When bulls initially put their head in the machine, pellets ‘dropped’, and kept dropping at specified intervals, to keep the bull’s head in the machine for at least two minutes. Air was then sucked into the Greenfeed machine to ensure all of the bull’s breath was captured, with sub- samples analysed for methane.

The bulls were allowed to visit the Greenfeed up to five times a day. The diagram on the right shows the key parts of the Greenfeed machine. After minor adjustments of methods and practice in using the machines, both LIC and CRV are confident that the planned trial design will work.

Preliminary breeding values are expected after one year, although three years of data will be needed to estimate breeding values with a suitable degree of confidence.

Genetic improvement is a slow game, but the process has begun, and the rewards are potentially significant for both farmers and other countries in the world.

This article was published in our Autumn 2021 Green to Gold publication.